In my short time on earth as someone who is relatively aware of how the institutions set up in society interact and link with one and another, I’ve learnt a lot about the place we live in. More than that however, I’ve learnt a lot about the opinions the public hold on current affairs and philosophical topics. As a general rule notwithstanding the occasional egregious exception, on anything from education to war you can expect a spectrum of differing opinions and theories on what the natural order of things are from hard left communist/socialist ideals to far right conservative ideologies. It goes without saying that some opinions and theories are more ‘scientific’ than others. But the one and only topic I’ve seen where most people seem to be united even if they don’t believe to be, would be that of the prisoner. Specifically, the function of prisons as an institution and what prisoners deserve as a result of their conviction.

Punishment = Justice?

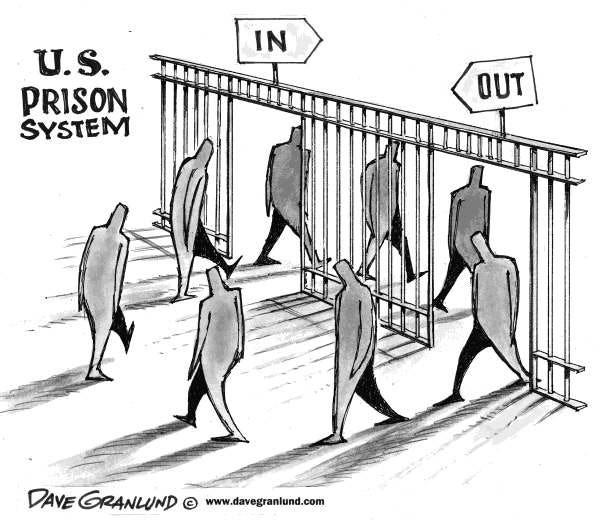

As a general unspoken rule of thumb, prison is viewed by the public as a place where morally bankrupt people go to as a punishment for violating the common values we have as a society, or in more liberal terms, a place for ‘rehabilitation’ . For this, we can thank age old traditions of punishment that have been perpetuated through many different types of societies and cultures, even upheld in media such as film, TV, journalism and so on. It’s a belief so deeply entrenched in society those privileged enough to not have been to prison or know anyone who has don’t second guess it, which is something that is immensely important to the upholding of the CJS as we know it. This is also a view shared by virtually every political leader and figure in the CJS, reflected in the ‘Tough On Crime’ rhetoric and policy that leaders we know and love have adopted through history such as Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher and Bill Clinton, which entails practice like mandatory minimum sentencing and the infamous 3 strike rule. And generally speaking, the average person doesn’t think twice about where that logic inevitably has led us to (the point we’re at now), nor do the real reason two as according to them, the average criminal lies anywhere on a spectrum from selfish to outright psychotic and therefore needs no afterthought.

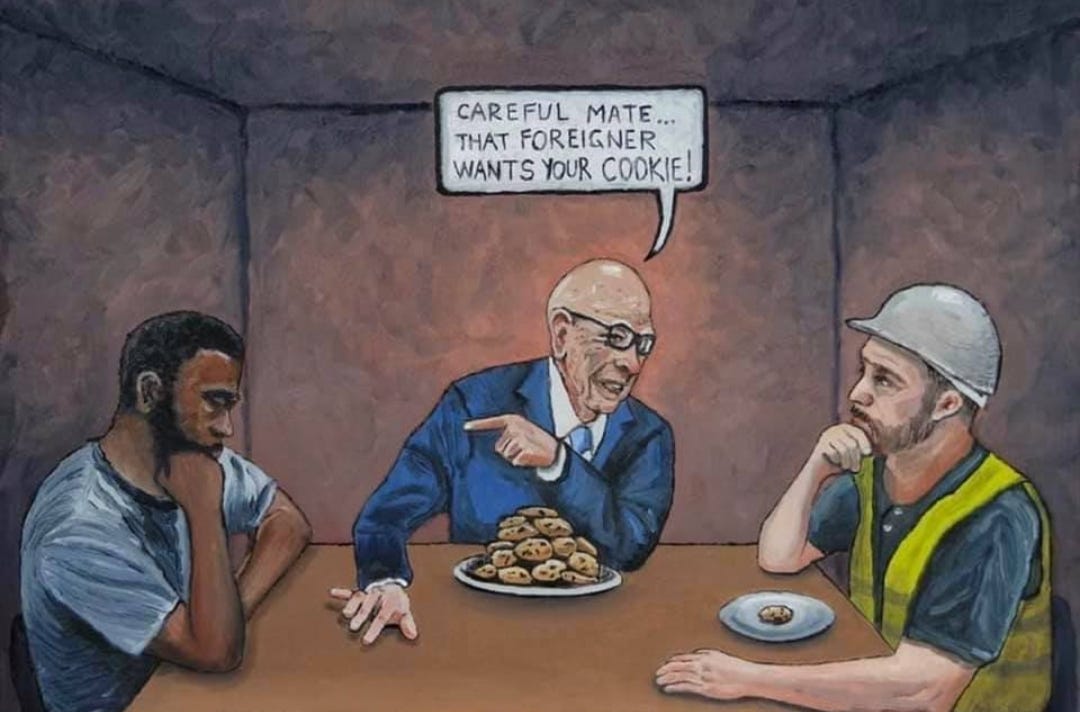

What we are then left with , is the stark difference in the reality of criminality and the ideology of punishment and population of control that we are brought up in. A foundational principle which has proved to be instrumental in the matter of criminal justice revolving around punishment in the way it does is the belief that every convict has a choice and made the wrong one. Essentially, crime is something avoidable and therefore choosing to do it deserves retribution. However, the reality of the condition of prisoners is much, much darker than just a question of morality. When you begin to look at institutions as organisms that interact with each other as opposed to isolated things, a picture of oppression and disenfranchisement is painted in place of the fear-mongering and ignorance we’ve become accustomed to in the west.

The myth of rehabilitation.

The Ministry of Justice in 2022 found that 57% of all prisoners in the UK, a self-proclaimed vestige for progression, could only read and write at the level of an 11 year old child. This coupled with staggering numbers such as 63% of prisoners having been suspended in school and 41% witnessing being witness to abuse in the house as children screams that there is desperately needed nuance in the discourse around the prison population which is intentionally ignored (Williams et al. , 2012). When we add the missing context of the marketisation of institutions such as education, leading to schools and those who work in them being geared towards churning out statistical results as opposed to the development and safeguarding of all children, we are faced with a population of fully grown adults who have, purposefully or otherwise, been left ill-equipped to serve as functioning citizens of the state.

When we shift our view of the prison population from solely perpetrators to allowing the possibility of them to be products of deprivation on all levels and the ensuing limited amount of choice they get presented with. Our understanding of criminality as a binary of morality, good and bad or righteous and selfish, is one that is shallow at best and insidious in its’ most potent manifestations. When we shun those who commit crimes that we have been told are exceedingly dangerous, and then don’t so much as spare a second thought for their condition in relation to ours, we allow for stigma to seep into our nature and blind us to the irrationality of punishment in imprisonment. No matter how harsh the penalty has become on crimes that have become the media’s folk devil and pushed to us as dire, heinous actions that jeopardise our way of life (not any white collar crime that ACTUALLY does this), crime persists and history repeats. And a big part of this, is the myth that prisons as we know it now are meant to rehabilitate. In reality, the institution of prison as we know it now is a mass production of labour extracted from prisoners for hours at a time at the minimum rate of 50p an hour (Mantouvalou, 2022). You might be encouraged to say that you don’t care about what happens to prisoners as it’s what they deserve, but in response to that I’d like to ask you who does it help in the grand scheme of things? Does violating the labour rights of someone convicted of armed robbery who is illiterate for years on end give them a diploma? Does it make that person more or less likely to come out as a functioning citizen? Does it make you and I any safer? And does it address the roots that led them down that path? Or is it just another way for corporations to line their pockets?

To those who are decently read on the topic of prison rehabilitation , or rather the lack thereof, nothing I’ve said is revolutionary at all. In fact, it’s quite a light sketch of a shadow that’s loomed over the working class of the global population for decades before I chose to say a word. However, I’d like to put forth the belief that being versed in, and even verbally AGREEING with the fact that punishment in the criminal justice system doesn’t help us isn’t enough. As we are all human, we all have our biases and personal limits as to what can be tolerated in our lives and what can’t, which is to be expected. But one thing I’ve observed is how in discourse surrounding this topic, even the most progressive people let their biases turn into stigma that mirrors the most bigoted rhetoric, leading them to be inadvertently complicit in the head turning ingrained into society that allows the criminal justice system to continue to serve capital gain as opposed to the interest of the people. In a bid to appear ‘down with the movement’, proclamations of abolition and prison reform are often heard from the people that do this, until we get to certain crimes that are an active danger. The rhetoric switches from people being products of society to personal responsibility and a lack of morality, without any deeper analysis using sociological framework.

The unforgivable crime.

For me, the most tragic case of this is that of the crime of Joshua Jacques. Joshua Jacques is a 29 year old man who killed his girlfriend Samantha Drummonds, her mother Tanysha Ofori-Akuffo, grandmother Dolet Hill and her grandmother’s partner Denton Burke in a single night on April 25, 2022 during a episode induced by cannabis intake. Police were called into Ms Hill’s home in Bermondsey to the sight of bodies and Jacques lying naked in the upstairs bathroom screaming “Allah, take me!”, “Kill me now” and “God please forgive me”. He was found guilty on 4 counts of murder.

What occurred here is a tragedy that has no rational excuse, nor do I bring it up to attempt to make one. But what I do want to highlight is not only the public reaction to the crime reported, but the history of Joshua Jacques and how it is an example of a precedent set by the criminal justice system and policy makers decades ago and how the two link to my overarching point. Upon this story being broken by major publications that have accounts on many social media platforms, there were many calls for a punishment that fits the crime, such as life in solitary confinement or the death penalty. And, make no mistake, I write this with no intention of slandering those that felt that way, nor do I think the emotions that led them to say these things are invalid. I just think the very real and potent calls for justice need to be aimed at a wider target than one man at a time.

Joshua Jacques had 11 convictions prior to this for 20 different offences, and his first mental health assessment was in April 2016 after seeking treatment for drinking water from a toilet. He was arrested after threatening to kill a security officer and threw food around his cell. In 2018, he was detained under the Mental Health Act and was in hospital from April 27 to August 7. He was sentenced to 51 months for conspiracy to deal heroin and crack cocaine in February 2020/ Days before the killing, he doubled his cannabis intake and Ms Drummonds confided in a friend that she believed Jacques was having an “episode” just one day before the tragedy occurred. When reading these facts rattled off in articles like unimportant background to the character of a heinous figure, all I really had in my mind was the question of what the criminal justice system did or didn’t do in the life of Joshua Jacques. In a criminal justice system where resources are funnelled towards the extraction of profit from prisoners and away from programmes and activity that aims to work toward rehabilitation, how many times have families been failed in the never ending war waged of punishment and population control? In a world where mental illness is increasingly criminalised, and exceedingly more so for black people, at what point do we begin to turn the finger that assigns blame towards the system that so often claims to stand for justice and rehabilitation of the convicted that pass through it but let things like these tragedies go unchecked?

What I’m not saying is that all convicts have no agency and are absolutely blameless. I think that’s as asinine and naive an argument as the one that they are to be blamed wholly and have all the facilities necessary to not commit crime and therefore should be punished for it. But what I do vehemently believe in is that we as people, whether we know members of the prison population or not, do have a responsibility to examine what we consider criminal and what we don’t. We should be for the rehabilitation of prisoners as well as the dismantling and re-imagining of systems that contribute to them being there, not only for their sake as rightful citizens of state, but for the sake of the population and our future so that we’re not left with more tragedies asking “who is to blame?” while the system that enables it runs rampant. And if you still disagree, I’d like to ask you who has asserted to us throughout history that there are certain crimes throughout history that need punishment, and does the punishment of a population by violating their human rights serve us, or the ruling class?

Bibliography

Mantouvalou, V. (2022). Pay for Work in Prison [online]. Available from: https://uklabourlawblog.com/2022/12/12/pay-for-work-in-prison-by-virginia-mantouvalou/

Ministry of Justice (2022). Prison education: a review of reading education in prisons.

Williams, K., Papadopoulou, V., Booth, N. (2012). Prisoners’ childhood and family backgrounds: Results from the Surveying Prisoner Crime Reduction (SPCR) longitudinal cohort study of prisoners

Very interesting article - I like the comments you made about how easy it is for people to fall into letting bias and stigma influence their words even if we are outwardly "down for the cause". I think you'd appreciate this lecture by this US law professor (who was a former prosecutor) about the faults in the criminal justice system - https://www.law.uci.edu/news/videos/CLEAR-Butler-lecture-2018.html